by Robin Dost

Since the beginning of this year, we have again observed an increased number of attacks by APT28 targeting various European countries. In multiple campaigns, the group actively leverages the Microsoft Office vulnerability CVE-2026-21509 as an initial access vector.

This article focuses on how CVE-2026-21509 is used in practice, how relevant IOCs can be extracted efficiently from weaponized Word documents and how the actors own geofencing can be leveraged to infer operational target regions.

Before diving into the analysis, a brief look at CVE-2026-21509 itself.

Understanding CVE-2026-21509 (Click)

CVE-2026-21509 is a Microsoft Office vulnerability affecting how embedded OLE objects are validated during document processing.

Microsoft classifies it as a security feature bypass, which is accurate, but undersells the actual problem.

Office makes trust decisions based on internal object metadata that originates directly from the document itself.

The vulnerability does not rely on macros, scripts or external templates, it is triggered during normal parsing of specially crafted RTF documents.

From a user perspective, the document appears inert. There are no prompts, no warnings and nothing that would suggest active content.

The exploit uses RTF control words such as \object and \objdata to embed raw binary data inside the document.

During parsing, Word reconstructs this data into in-memory OLE structures, effectively rebuilding Composite File Binary objects on the fly. This reconstruction step is where the vulnerability is exposed.

The reconstructed OLE objects are deliberately malformed. Their headers look plausible, but their internal structure is inconsistent. Strict parsers reject them. Word does not. It continues processing and enters code paths that assume a coherent internal state.

Observed samples frequently use OLE Package objects and legacy COM class identifiers associated with historically risky components.

By manipulating how these objects are represented internally, Office checks meant to block them are bypassed, not by disabling protections, but by misleading the logic that decides whether those protections apply.

The document itself contains no payload. Its sole purpose is to reach a state where Office processes an object it should not trust.

Any follow-on activity happens later and outside the document.

This separation between exploit and payload fits well with current intrusion chains.

From a defensive POV, this explains why CVE-2026-21509 is easy to miss.

Static analysis shows no macros, no external relationships and no obvious indicators.

The malicious structures only exist after Word reconstructs them, which places the exploit below the visibility of most document scanning and macro-focused controls.

tldr;

CVE-2026-21509 is a Microsoft Office vulnerability that allows attackers to bypass internal security checks when Word processes embedded OLE objects.

The issue is triggered during normal document parsing and does not rely on macros, scripts or external content.

A specially crafted RTF document embeds malformed OLE objects that Word reconstructs in memory.

Office then makes security decisions based on this reconstructed data, even though it originates from the untrusted document.

By manipulating that data, an attacker can cause Word to accept and process objects that should normally be blocked.

The document itself contains no payload and appears harmless under static analysis. Exploitation happens entirely inside Words parsing and object handling logic, below the level where most document scanners operate.

Analyzed Samples

For this analysis, I looked at the following samples:

| Hash | Download |

| c91183175ce77360006f964841eb4048cf37cb82103f2573e262927be4c7607f | Download |

| 5a17cfaea0cc3a82242fdd11b53140c0b56256d769b07c33757d61e0a0a6ec02 | Download |

| b2ba51b4491da8604ff9410d6e004971e3cd9a321390d0258e294ac42010b546 | Download |

| fd3f13db41cd5b442fa26ba8bc0e9703ed243b3516374e3ef89be71cbf07436b | Download |

| 969d2776df0674a1cca0f74c2fccbc43802b4f2b62ecccecc26ed538e9565eae | Download |

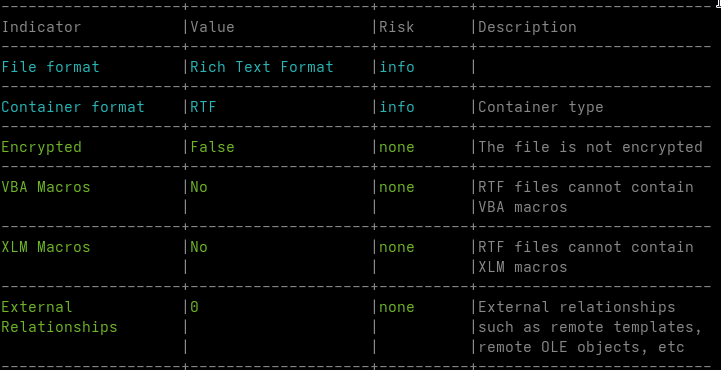

When I receive potentially malicious Word documents, my first step is usually to run oleid. In most common malicious documents, this already reveals macros, external references or other active content.

In this case, oleid reports a clean file. No macros, no external relationships, no obvious indicators.

This is expected.

The document is not a classic OLE container but an RTF file. In RTF, embedded objects are stored as hexadecimal data inside the document body using control words such as \object and \objdata. These objects do not exist as real OLE structures until Word parses the document and reconstructs them in memory.

oleid operates at the container level. It can only detect features that already exist as structured objects in the file. Since the embedded OLE data is still plain text at this stage, there is nothing for oleid to flag.

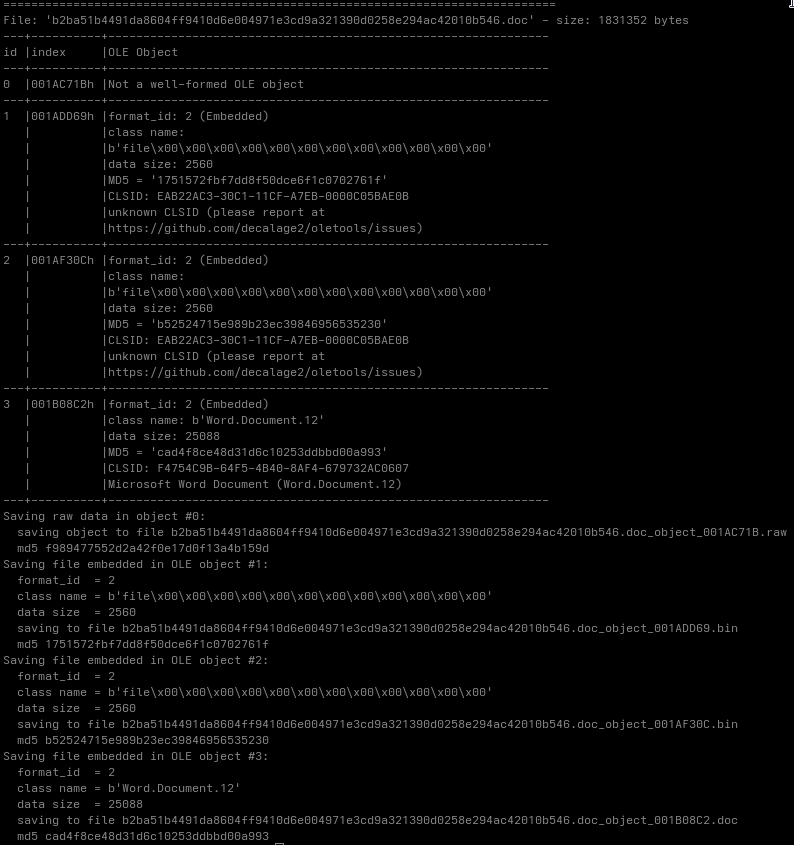

The exploit surface of CVE-2026-21509 only becomes visible after this reconstruction step. Tools like rtfobj replicate this part of WordS parsing logic by extracting and rebuilding the embedded objects from the RTF stream.

rtfobj -s all b2ba51b4491da8604ff9410d6e004971e3cd9a321390d0258e294ac42010b546.doc

Once reconstructed, the embedded objects are clearly malformed. They resemble OLE containers but fail validation by strict parsers, which is exactly the condition the vulnerability relies on.

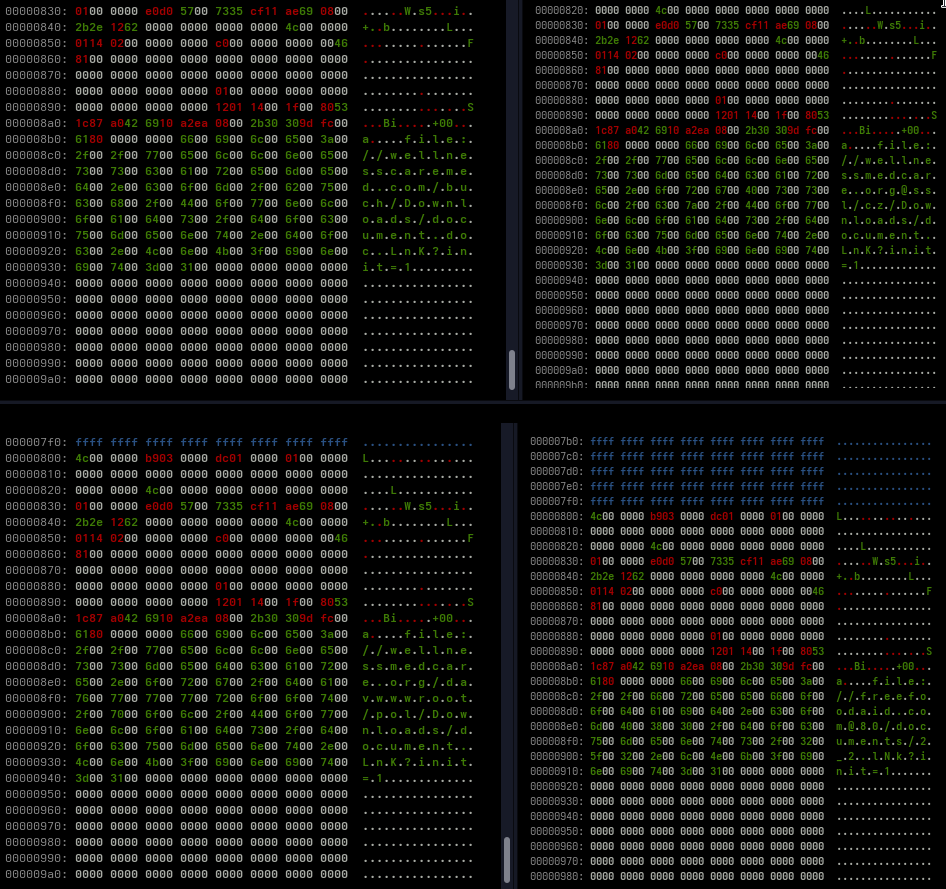

After extracting the embedded objects, I inspected the resulting files using xxd. At this stage, strings did not yield anything particularly useful, which is not surprising given that the document is not designed to carry a readable payload.

From this data, the following strings could be extracted:

| file://wellnessmedcare.org/davwwwroot/pol/Downloads/document.LnK?init=1 |

| file://wellnessmedcare.org/buch/pol/Downloads/document.LnK?init=1 |

| file://wellnessmedcare.org@ssl/cz/Downloads/document.LnK?init=1 |

| file://freefoodaid.com@80/documents/2_2.lNk?init=1 |

Why file://…/davwwwroot/...lnk is used

Paths likefile://wellnessmedcare.org/davwwwroot/pol/Downloads/document.lnk?init=1

are chosen to force specific Windows and Office code paths.

Using file:// changes how Office interprets the access. The resource is treated as a file system object, not as web content. This affects which security checks are applied and how trust is evaluated.

Mark-of-the-Web handling and web-centric protections do not apply in the same way as they would for http or https.

The davwwwroot path forces WebDAV.

This causes Windows to access the resource via the WebClient service, exposing the remote content as a network-like file system.

WebDAV remains a special case in Windows, where remote files are often handled similarly to local or SMB resources.

The .lnk file is the actual target.

The Word document contains no payload and performs no execution itself.

Its sole purpose is to reach a state where access to the remote resource is allowed.

Shortcut files are attractive because they can execute commands or load further components while being subject to different checks than executables or scripts, especially when accessed through WebDAV.

The query parameter is client-side only.

It is used to avoid caching and to reliably trigger initial access behavior. It has no functional relevance for the server.

In the context of CVE-2026-21509, this fits cleanly.

The vulnerability causes Office to make incorrect trust decisions during document parsing.

Once that decision is made, accessing a remote shortcut via a file:// WebDAV path becomes possible without macros, scripts or explicit downloads.

Identifying Targets

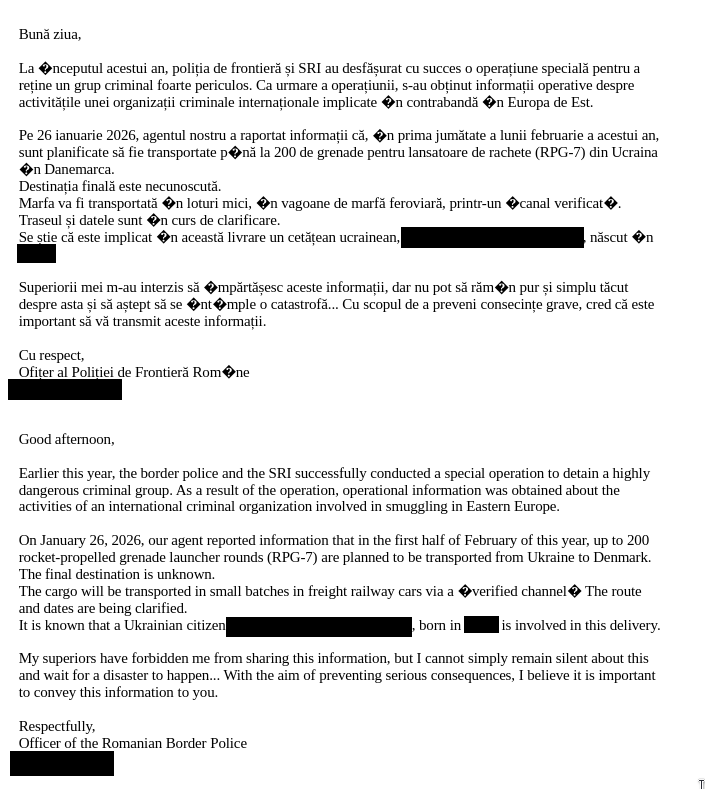

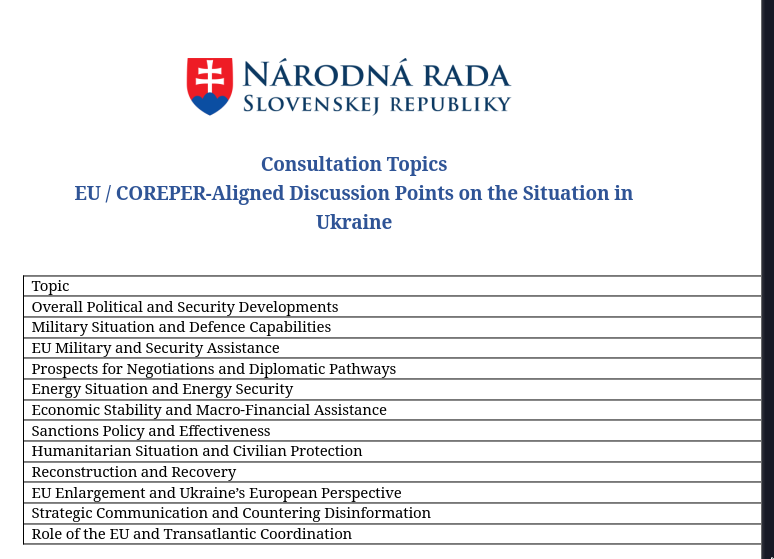

While analyzing the documents and extracted URLs, it became apparent that they reference potential target regions:

/cz/-> Czech Republic/buch/-> Bucharest / Romania/pol/-> Poland

Additional indicators inside the Word documents further support this assessment:

- Romanian language content

- References to Ukraine

- Mentions of Slovenia

- EU-related context

None of this is accidental.

At this point, the next step is validation. Russian threat actors are known to rely heavily on geofencing and APT28 is no exception. Fortunately, this behavior can be turned into a useful source of intelligence for us ^-^

Turning Geofencing into Intelligence

The first step was to take a closer look at the domains extracted from the samples:

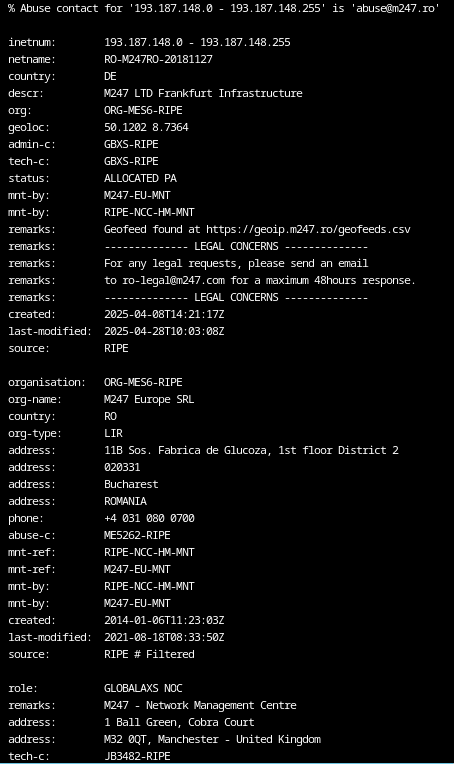

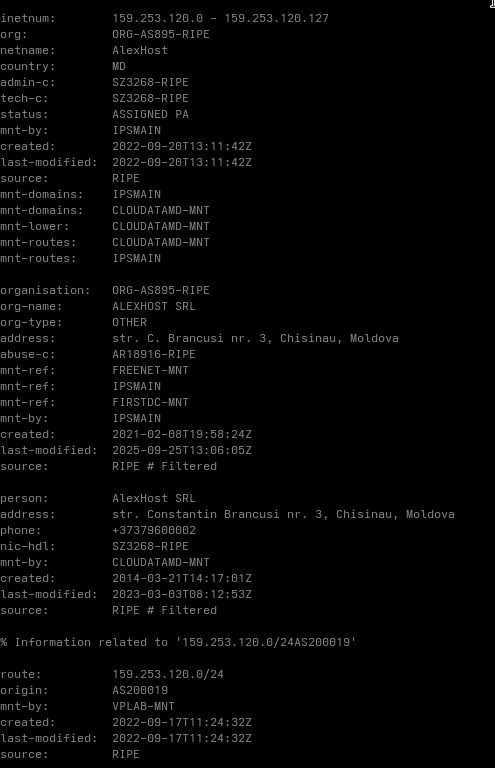

| wellnessmedcare.org | 193.187.148.169 |

| freefoodaid.com | 159.253.120.2 |

What stands out here is the choice of hosting locations.

Both IP addresses resolve to providers in Romania and Moldova. It is reasonable to assume that these locations were selected based on the campaigns intended target regions.

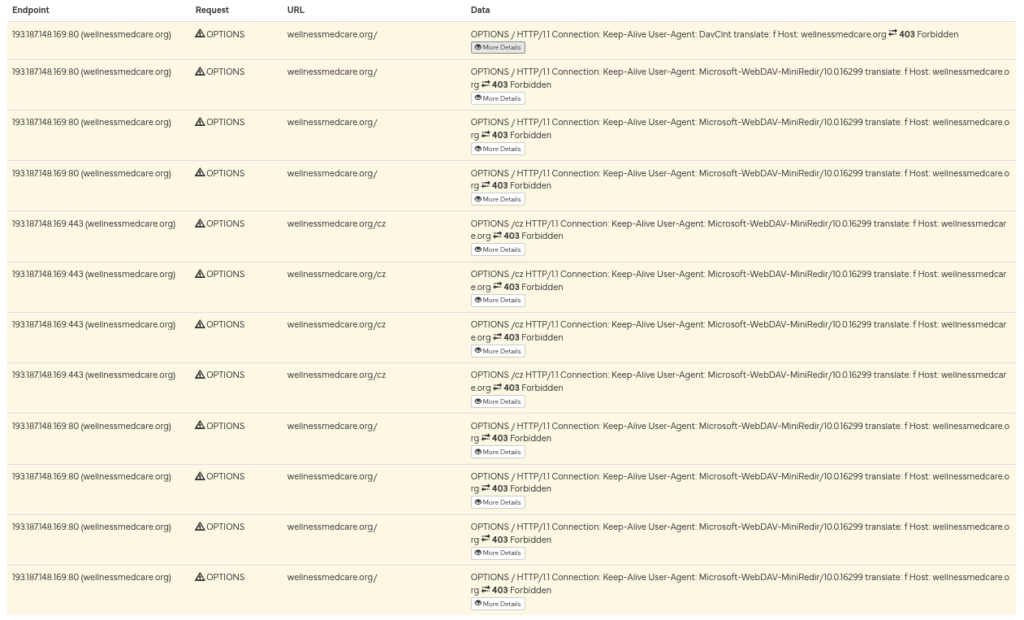

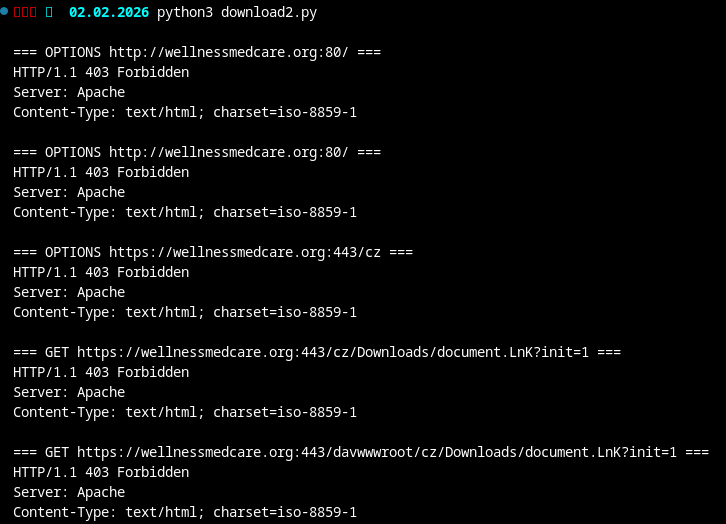

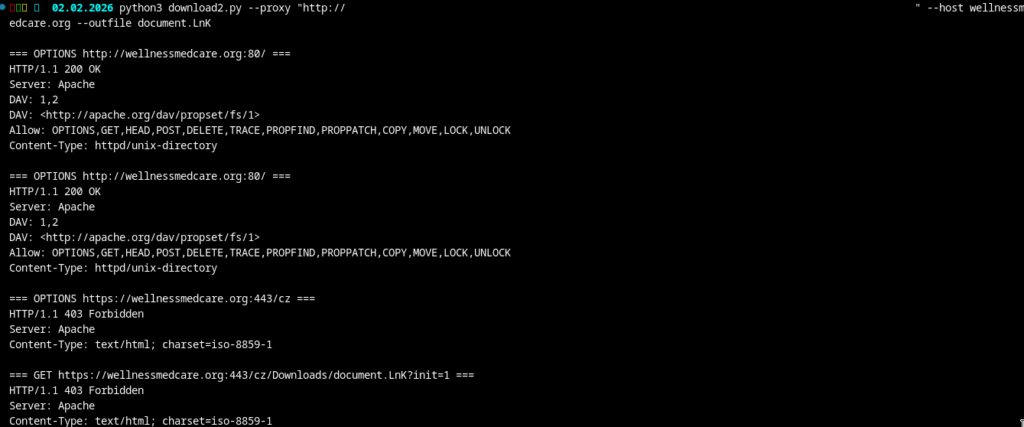

Next, I attempted to replicate the WebDAV requests generated by Windows in order to test the observed geofencing behavior.

To do this, I executed the document in a sandbox and captured the resulting network traffic.

Geofence Analysis

To validate the geofencing, I needed to determine which proxy locations were required to access the malicious resources without being blocked.

After identifying suitable proxies, I performed test requests using a custom script, once without a proxy and once using a Romanian proxy.

Without proxy:

With proxy:

The result is fairly clear. Requests originating from outside the expected regions are rejected with HTTP 403, while requests routed through a Romanian proxy succeed. This pattern can be used to validate likely operational target regions.

Out of 114 tested countries, only three were allowed access: Czech Republic, Poland and Romania. This aligns perfectly with the indicators observed earlier in the documents and URLs.

As this example shows, defensive measures such as geofencing can provide valuable intelligence when analyzed properly. Even access control mechanisms can leak information about an actors operational focus if you know where to look.

The second domain, freefoodaid.com, was already offline at the time of analysis. Given how short-lived APT28 infrastructure tends to be, this is hardly surprising. It is reasonable to assume that similar geofencing behavior would have been observable there as well, but for demonstration purposes, the remaining data is more than sufficient.

How to protect against these attacks

Update Microsoft Office and enforce a structured update routine.

Treat unexpected Word documents as untrusted and have them analyzed before opening them.

(or stop using windows :3)

Conclusion

CVE-2026-21509 works because it fits neatly into how Office processes documents today.

The exploit relies on internal object reconstruction, not on macros or embedded payloads, which makes it easy to overlook during initial analysis.

The surrounding tradecraft follows a familiar pattern.

WebDAV paths, remote shortcut files and strict geofencing have been used by APT28 before and continue to show up in current campaigns.

The technique is stable, requires little user interaction and avoids most of the controls that organizations typically rely on.

At the same time, this setup exposes useful signals.

Geofencing decisions, hosting locations and access behavior provide insight into intended target regions when tested systematically.

In this case, the infrastructure behavior aligns closely with the indicators found inside the documents.

From an analytical perspective, the value lies less in the exploit itself and more in what can be inferred from how it is deployed and constrained.